Engaging News Project’s Quiz Creator is by far the biggest product I have ever designed and developed. Over an eight month period, I did all planning, design, development, architecture, testing, documentation, and deployment.

To give you an idea of what goes into building a professional web application, I’ve documented the overarching phases of the project.

Planning

[rsp_img id=”2087″ align=”center” size=”full”]

It’s essential to identify your overall project goals first. These guide every decision throughout the entire project.

Goals should be measurable, and for the Quiz Creator, our main goal was to have ten second tier news organizations regularly using the quiz tool. As of this writing, we’ve only soft-launched the Quiz Creator, so we won’t be able to analyze if we were successful until our marketing efforts are in swing.

After the goals were identified, I worked on:

- User Stories to identify common user types and what their needs are.

- Competitive Analysis to see what the current market offers and how we can improve and build upon that.

- Documenting the Current Quiz Tool. As this was a rebuild of their existing tool, I was able to use the current implementation to identify used features and pain points, and use the database to research which features were used and which were overlooked.

- User Flow broken down by page and component to figure out exactly what a user would need or want to view at that time.

- New Ideas were jotted down as I went through the above stages, and fleshed out when/if they were relevant to a component.

Planning is the foundation for the whole project, so make sure it’s sturdy before you move on.

Sketching

[rsp_img id=”2107″ align=”center” size=”full”]

Sketching is one of my favorite parts of any project. I think I could use a ruler to draw straight-lined boxes all day. Maybe it’s because I was a huge hippie in my twenties with curvy lines everywhere and now I’m over-compensating.

Really, I think I love sketching because this is where the problem solving and strategy start to come together. Sketching allows me to evaluate lots of different possibilities quickly.

Because I’ve already planned out what elements need to be on each component, I can read my notes on what needs to be included and why. You shouldn’t be adding new elements while you sketch, you should be figuring out how to display those elements.

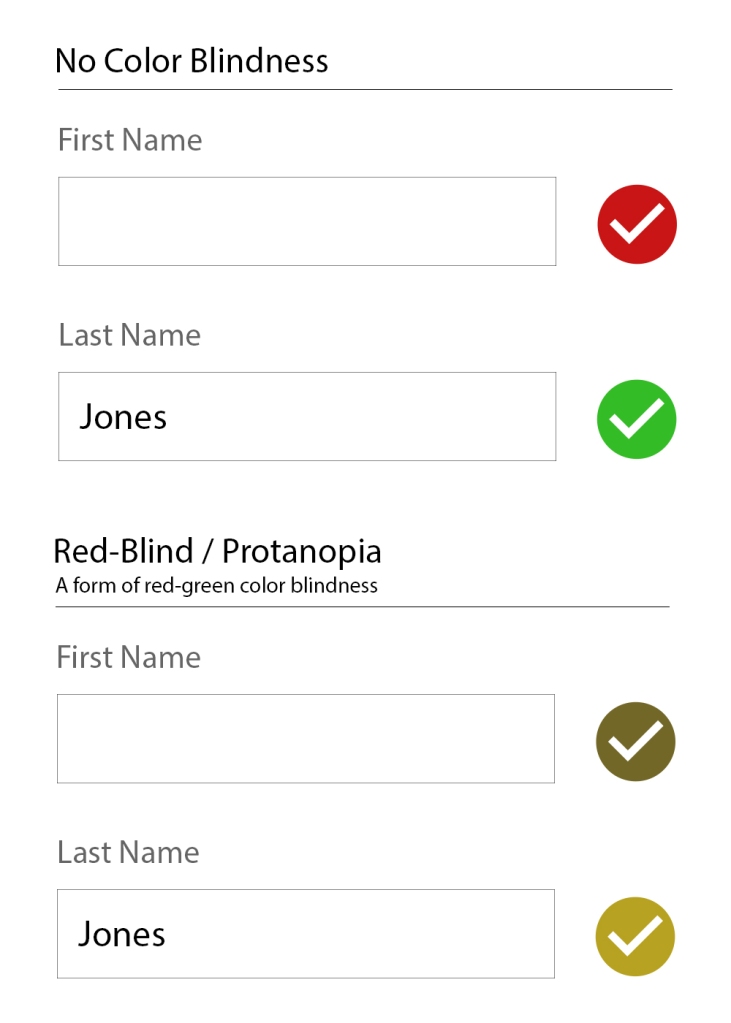

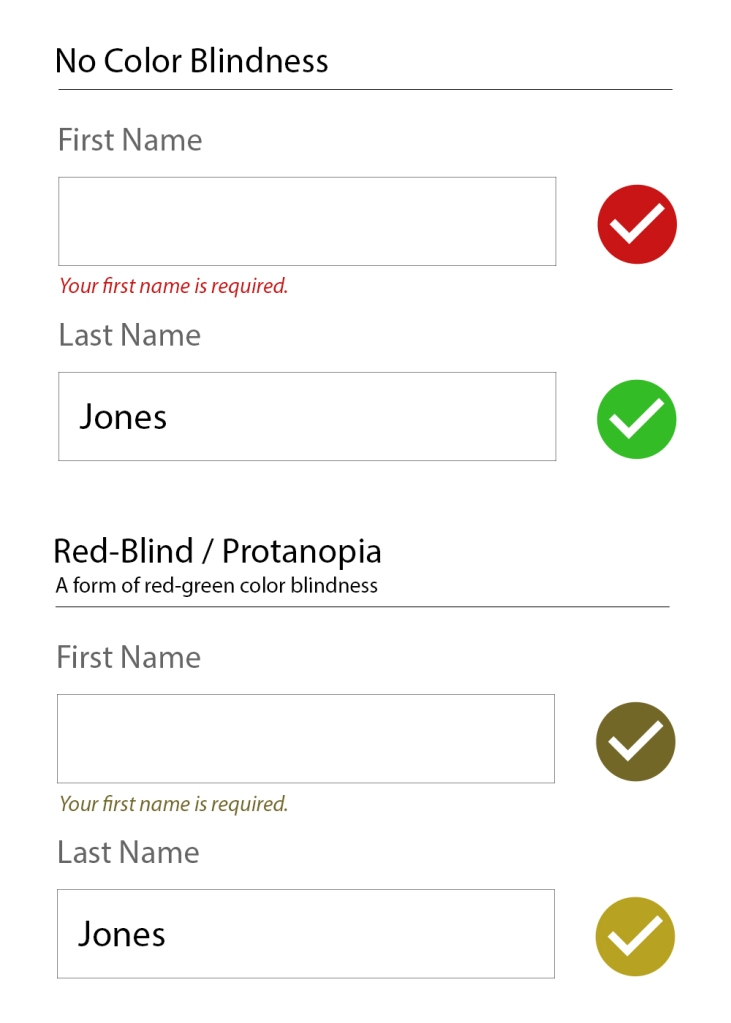

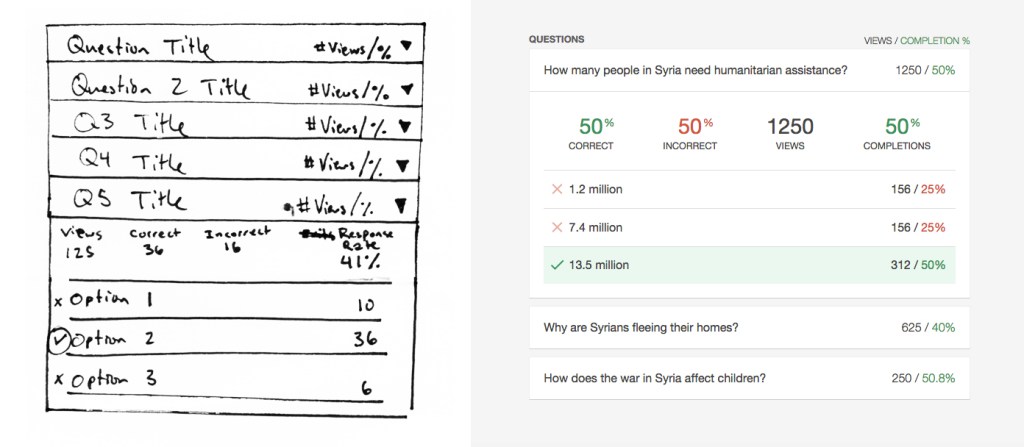

Here’s a sketch of a component where people will view the individual question results from a quiz they created alongside an image of the completed component. The sketch is rough, but it shows the key elements that will be included and their placement. Also, note that it’s an oddity that the sketch matches the final component. Generally things change a lot more between sketch and completion.

[rsp_img id=”2112″ align=”center” size=”full”]

Once you’ve built and tested a lot of websites, you can visualize how someone would use the website and identify common traps. A five minute sketch can end up saving weeks of development time wasted on a bad idea.

Testing

Testing is an ongoing process, and it begins at sketching. I show people my sketches with a few directed questions and see if they understand what the components are how they would use them.

Throughout the entire project, keep testing. These are generally informal at the beginning, and become more formal near the end of the project.

For the Quiz Creator, I tested my sketches and prototypes informally, and then tested different elements of the production version as features were completed. Testing was done via Skype with willing members of the Engaging News Project team. I’d give them a task, such as “Publish a three question quiz,” and take copious notes on what they did, focusing on what was difficult for them to accomplish.

Just as sketching can save you weeks of development, testing reveals issues you’ve missed or overlooked in your planning. The earlier you can identify these issues, the more time you’ll save. Test early, and test often.

Prototyping

Prototyping is used on designs that seem to pass muster, to see if they really do, indeed, pass muster. A lot can be gained by looking at a sketch on paper, but it’s another thing entirely to interact with it.

I go as fast as I can on prototypes, not worrying about making things responsive or production-ready. There’s no database to interact with, and most elements are dropped in to get the idea across, not to be perfect.

Here’s a series of my initial sketch for the add question view and how it changed from sketch through prototypes to final product.

[rsp_img id=”2137″ align=”none” size=”full”]

[rsp_img id=”2120″ align=”none” size=”full”]

[rsp_img id=”2115″ align=”none” size=”full”]

[rsp_img id=”2117″ align=”none” size=”full”]

The one thing to spend more time on fine-tuning is what you think your client will be focused on. I knew the people reviewing the project were likely to get hung up on incomplete visual styles, so I polished up the typography and base styles. They were not perfect, but they were good enough to not be a distraction to people reviewing the prototype.

Prototyping saved me a huge amount of overhead because I didn’t spend time implementing a complex system that would end up not working. When I built the production version, I was confident in the application, and usability testing confirmed that creating quizzes was an easy process.

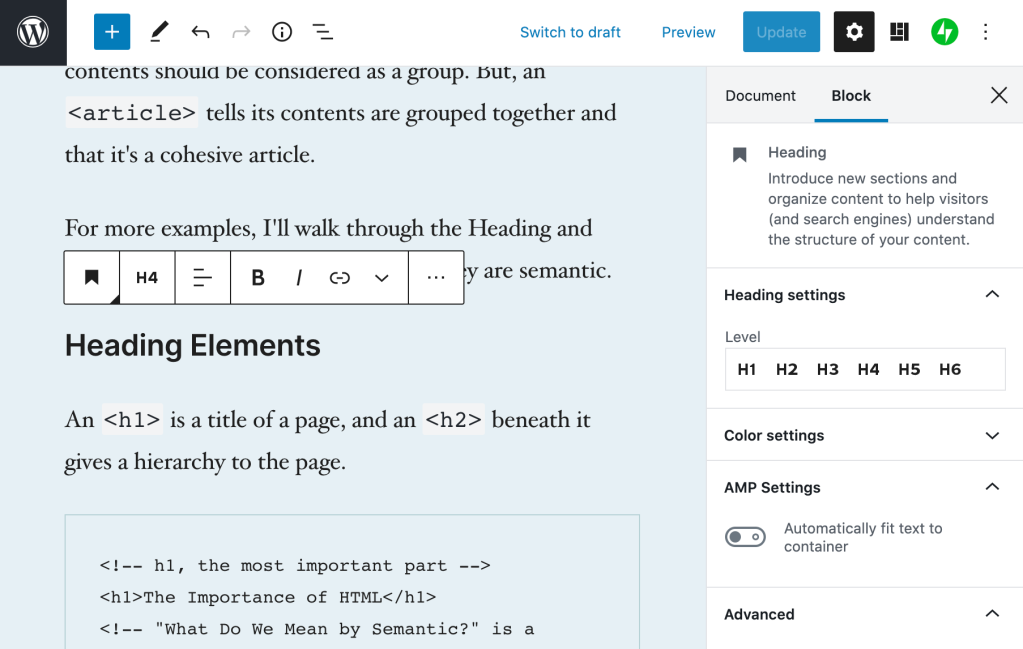

Architecture

I’m mainly a designer and front-end developer, so this project was my first complex database build. If someone had told me that you get draw a bunch of straight lines when designing databases, I probably would have done this years ago.

[rsp_img id=”2104″ align=”none” size=”full”]

The rule of thumb for designing a database is to get it 90% complete before you start coding. You won’t get 100% coverage because you can’t foresee every possible scenario you’ll need, but if you’re 90% there, you have a strong foundation that will probably be able to accommodate anything you throw at it.

At the same time as designing the database structure, I was working on how best to architect the methods that the Quiz Creator would interact with its own database as well as the site’s WordPress database. It was a project requirement for the Quiz Creator to be built on WordPress, but I wanted to make sure that:

- the plugin could be extracted in the future for other platforms without having to completely rebuild it,

- the database could live entirely outside of the WordPress database for speed and managing heavier loads,

- and, most importantly, quizzes could be embedded independently without firing up WordPress core.

This was one of three ideas I sketched out on how the code should interact with the database to be robust, independent, maintainable, and extensible.

[rsp_img id=”2109″ align=”none” size=”full”]

Build

Now that everything was in place and most of the big ideas had been figured out, I started coding the production version of the Quiz Creator. This was by far the longest part of the project, but things came together smoothly because of the extensive planning. Without planning, the coding would have gone as well as trying to build a house without a blueprint.

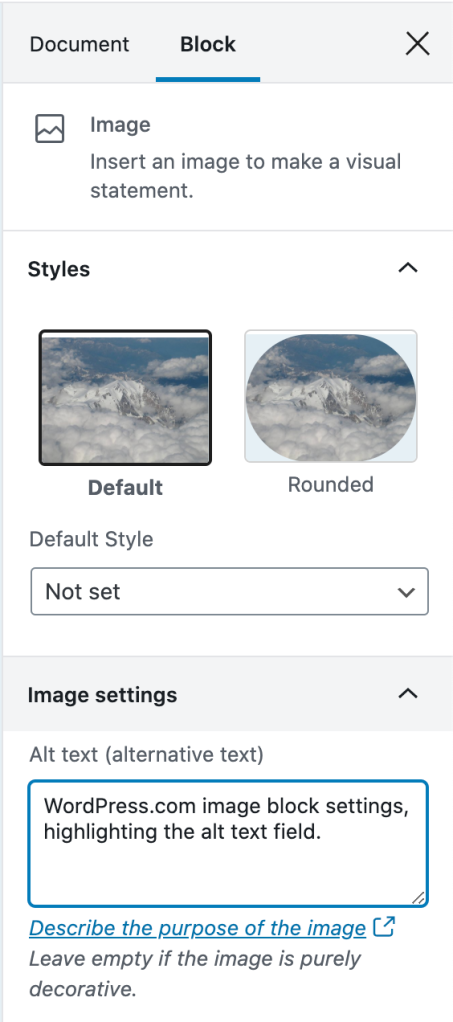

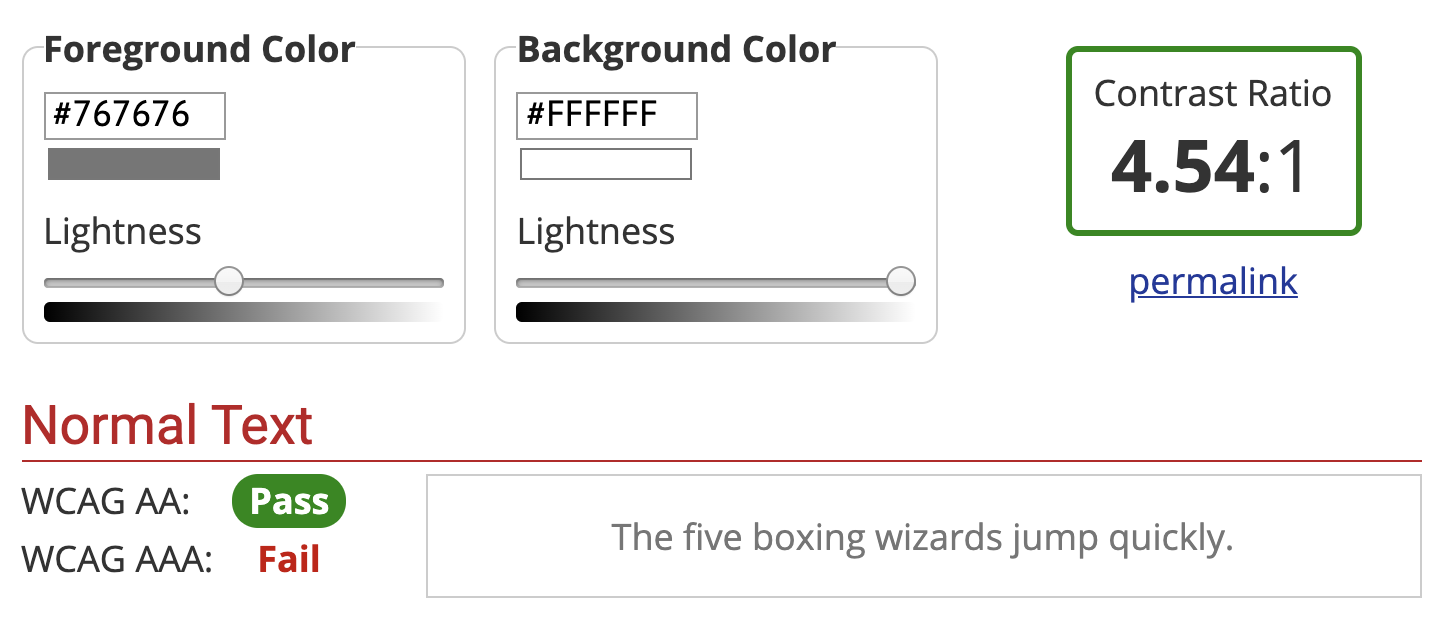

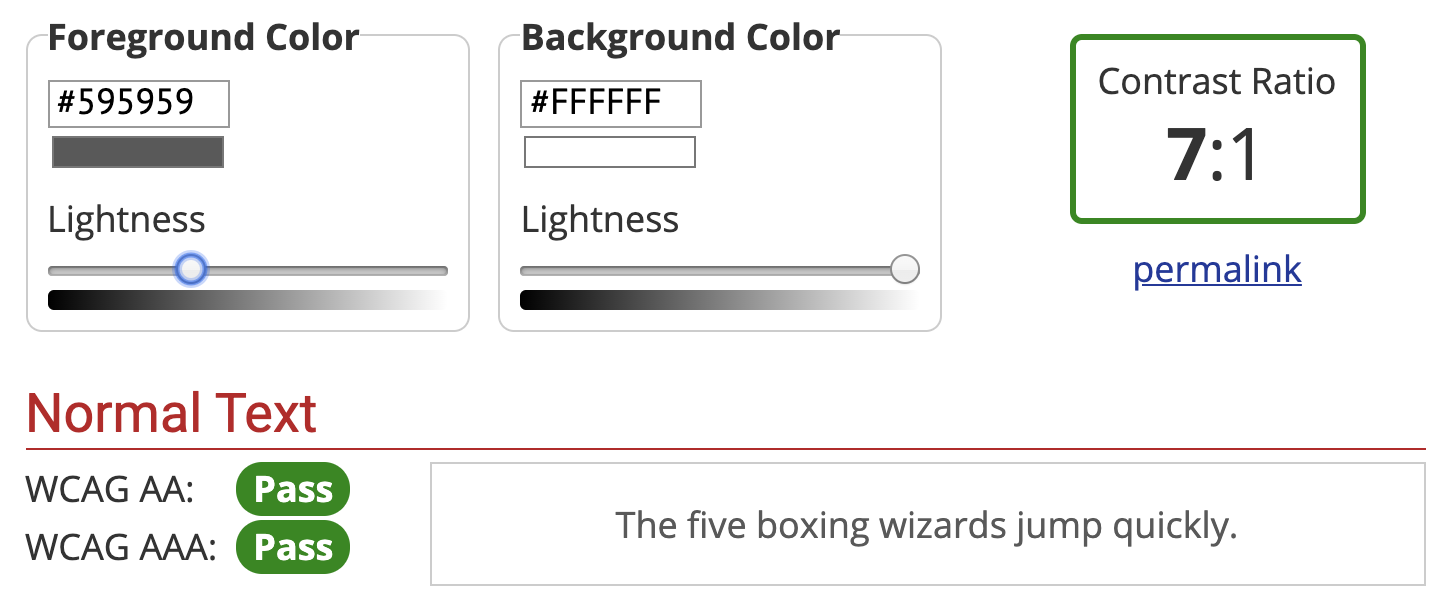

I utilized ideas from progressive enhancement, responsive design, and web accessibility to make sure people had a great base experience on any device with any connection. The embeddable quizzes I went one step further on, and made sure you could take quizzes without cookies or localStorage. Everything is keyboard operable and screen reader friendly, and JavaScript is an enhancement, not a dependency.

For tooling and coding (and to make sure I get to list all the hippest acronyms), I used:

- Semantic HTML with ARIA Attributes where necessary

- SCSS with classes using the BEM naming convention

- JS

- Gulp with BrowserSync, libsass, and some nice concatenators and minifiers for good measure

- Git & Github

- Terminal

- Atom Editor

- Object Oriented PHP

There are many ways to build a site, but as long as it works quickly on any device and plays well with assistive technology, I’ll be happy with its codebase.

Performance

Performance is a consideration throughout the entire project (even when sketching!), but at the end is when analyzing performance across the wire makes the most sense. The lowest hanging fruit is minification and combining files. I focused on the embeddable quizzes the most, as I didn’t want people embedding bloated quizzes onto their sites.

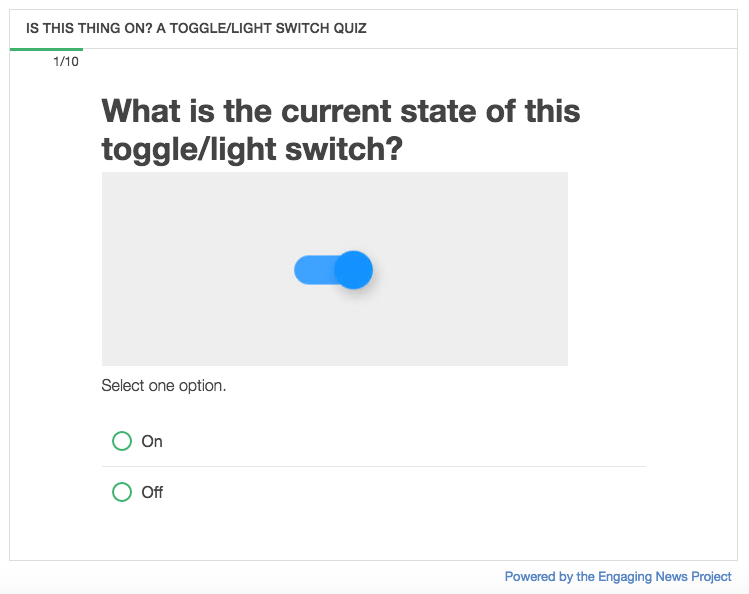

In the end, the final embedded quizzes only load 7 files for a total of 75kb. Here’s a quiz built using the Quiz Creator where two of the answers are in the previous sentence.

Also, make sure you’re caching your resources and that everything is gzipped.

Analyze and Refine

Because this project just launched, I don’t have any data to analyze yet. Once I do, I’ll be using Google Analytics to look for:

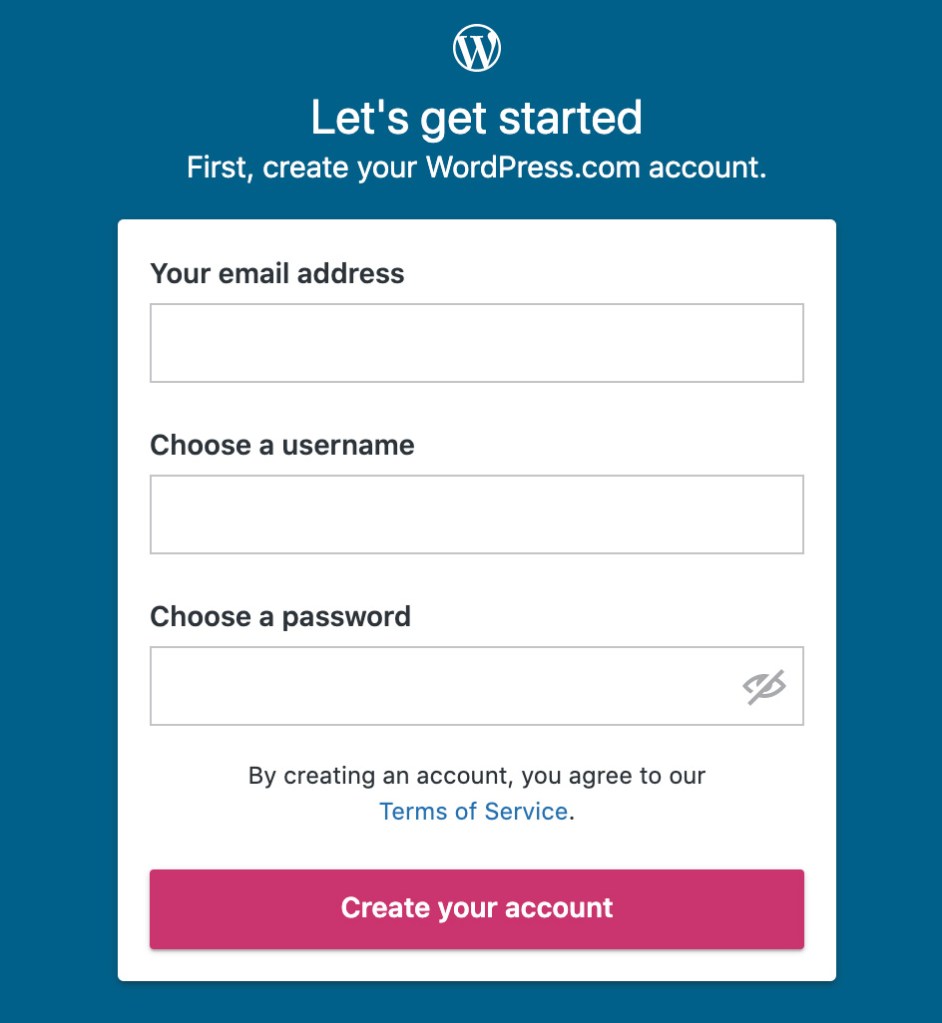

- What percentage of people arrive at the marketing page and end up registering for an account?

- What percentage of those people complete the process and embed a quiz?

- If they don’t embed a quiz, where do they fall off in the process?

- What percentage of people create and embed multiple quizzes?

Once I have those numbers, I can use the Quiz Creator database to anonymously look at how people are using the Quiz Creator, and hypothesize what things may contribute to people becoming long term users vs people who don’t end up embedding a quiz at all.

A few possibilities might be:

- Maybe if someone embeds a quiz that gets at least 1000 responses, they’ll be more likely to create another quiz.

- Maybe people publish a quiz, but need more help with the embed process.

- Maybe the benefits of using a quiz isn’t clear enough on the marketing page.

Using the data collected, I can save time by making better guesses. Then, I can test new ideas to improve conversion rates against the current version via AB Testing or Multivariate Testing.

Applicability to Other Projects

The Quiz Creator was a huge project, but you can use these same concepts for anything you build on the web, big or small. It could be an entire rebuild, or as focused as trying to improve conversion rates on a sign-up form.

Here’s a quick recap of the process.

- Plan: Identify a measurable goal you want to accomplish.

- Sketch: Problem solve ideas on how to accomplish your goals using pen and paper.

- Test: From here on out, test everything, and test often.

- Prototype: Use the medium you’re building for, and quickly prototype examples of your sketches to see what works and what doesn’t.

- Architect: Before you start coding, make high-level decisions on how pieces of the application will interact with each other.

- Build: Make it happen.

- Refactor: Improve performance by minification, reducing the number of files loaded, caching, and more.

- Analyze and Refine: Gather data on how people are using your application, and use AB testing to improve conversion rates in key areas.

Processes vary from person to person and at different organizations, but this is what I’ve found works well for me and produces good outcomes for my clients.