Web accessibility shouldn’t be an afterthought, but, oftentimes, it is. Fortunately, for most basic sites, it’s easy to make some minor adjustments that make a huge difference in the site’s accessibility. I recently retrofitted some of my designs and code to be more accessible, so here’s a few quick tips I picked up along the way.

Be Descriptive with Your Links

Imagine what your link text sounds like out of context. “Click here” doesn’t tell us where we’re going. “Dessert Recipes” or “Chillin’ Beluga Whale” do, however. If you click, “Chillin’ Beluga Whale,” you have a pretty good idea of what you’re in for.

All the people who clicked the Chillin’ Beluga Whale link just got a huge dose of plump, alien-looking beluga whales who just want to reelaaaaaaax, man.

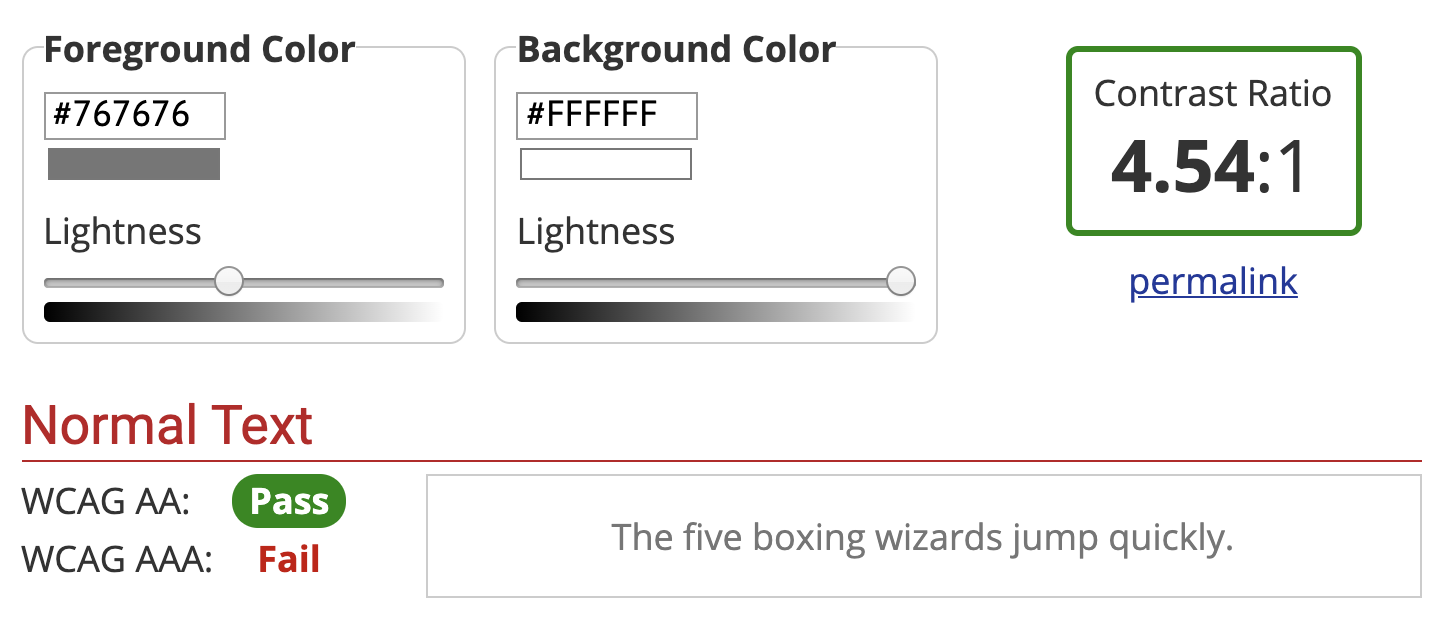

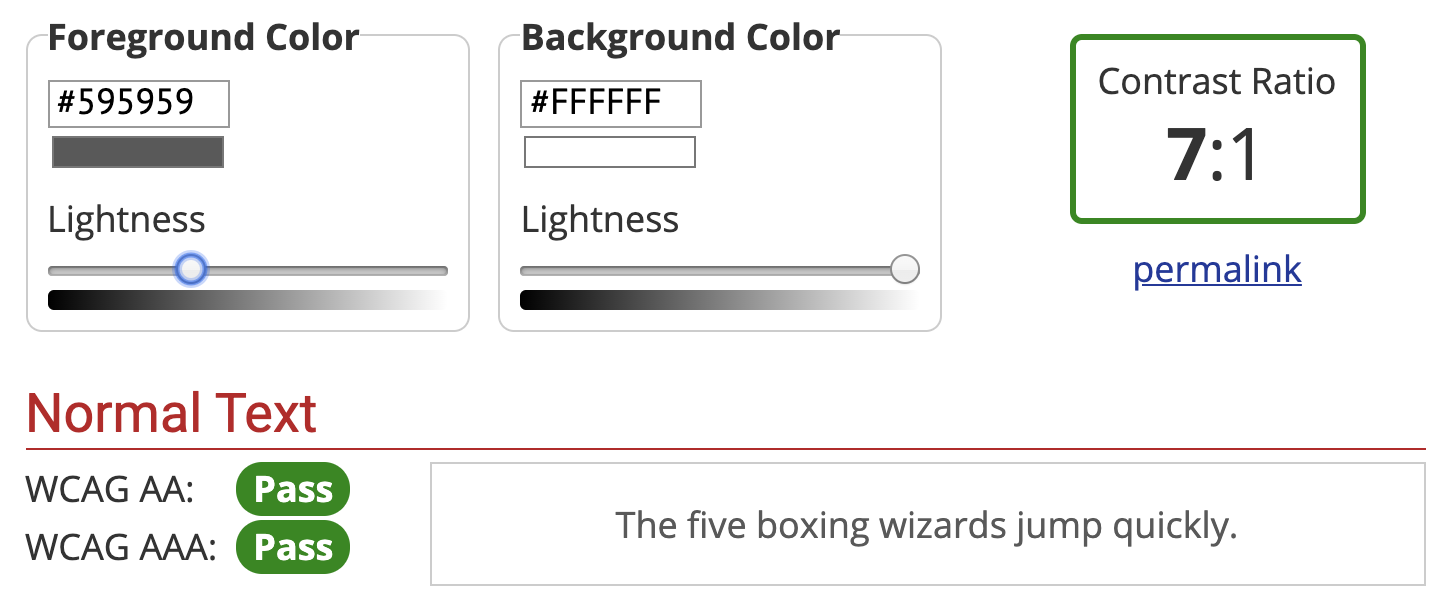

Check Your Design’s Color Contrast

Shoot for at least a contrast ratio of 4.5 to make sure people can easily read your content. Use this contrast ratio tool to test your color combinations.

For example, I just checked my link contrast for the first time, and it’s only 2.2. I need to change the color, even though I spent waaaaay too long picking out the one I felt was best for the design. Poor me…

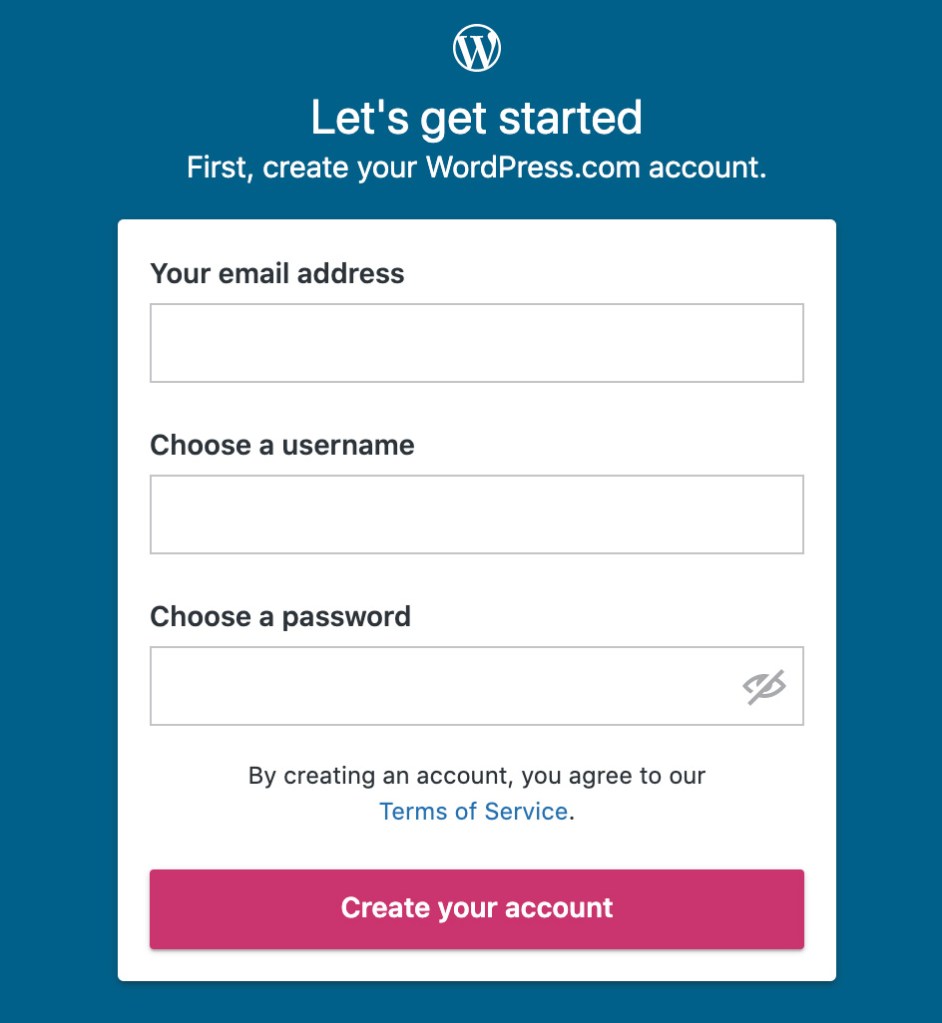

Since getting into web accessibility, I’ll turn on my screen reader and test sites when I’m ordering something. It’s amazing how difficult to use some of them are. For example, if a site only uses placeholder text to communicate a text input, the screen reader reads to me “Edit text, blank.”

That’s it. “Edit text, blank.”

So, if I was trying to fill out this form without seeing it, all I’d know is that I can edit text, and that the field is currently blank. Not very helpful as to what I should actually type.

Here’s a better way to do it:

<label for="email">Email</label>

<input id="email" name="email-address" type="text">

Or, you can wrap the label, but make sure to still use the ‘for’ and ‘id’, as not all screen readers handle it right without it.

<label for="email">Email

<input id="email" name="email-address" type="text">

</label>

Make sure the label for=”” and input id=”” names match. That tells screen readers that this label is for that input. Now, when a screen reader announces that input, it’ll say, “Email. Email, edit text.”

Much better.

Don’t Use maximum-scale=1 in your Viewport Meta Tag

Ever been to a site on an iPhone where you wanted to pinch-to-zoom to see an image larger, but it didn’t work? It’s probably because maximum-scale=1 was used.

maximum-scale=1 removes the ability for users to zoom in on the page. Start zooming on a few random pages on your smart phone. It’s unfortunate how prevalent this issue is.

A better way to do it is to set the initial-scale, then let your user decide if they want to zoom or not. This is the meta viewport code I use on my sites.

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

This issue highlights a good rule of thumb: Don’t remove features that are meant to improve accessibility.

Don’t Remove Focus Outlines on Links

I’m guilty of this. On most of my early sites, I wanted to remove those “ugly” outlines that appeared after you clicked an internal link.

“I don’t use a keyboard to navigate the screen, so my users don’t use keyboards either!” I thought.

For those who don’t, having a slight outline to show tab focus doesn’t make them fly into a rage and smash their fists on their computer. For those who do use a keyboard to navigate, removing the focus makes the website significantly less usable.

The pros/cons of this are pretty clear. Remember, don’t remove features that are meant to improve accessibility.

Don’t Open Links in New Tabs

SEO, keywords, link juice, umm… mumbo jumbo…?

It may come as a shock to you, but, I’m not an SEO person. So, I don’t know the implications of not using target=”_blank” to open external links in a new tab. But, I do know that when you use a screen reader and you click on a target=”_blank” link, it’s really vague that you just opened a new tab. It’s really easy for it to slip by you, or not be announced, so you don’t KNOW you’re on a new tab.

Here’s the process, as I imagine it:

- Click link.

- Link opens in new tab, but you don’t know you’re on a new tab.

- You read for a minute on the new tab.

- All done. Time to go back to the previous page.

- *Do keyboard shortcut for going back in the browser*

- *Computer doesn’t do anything, because… there is no going back.

- *Reflect on the heaviness of this deeply meta situation*

- *Eventually, hopefully, realize you’re on a new tab and use the tabs to navigate to where you were*

- *Say a short-but-sweet curse upon people who code links to open in new tabs*

So, yeah, don’t do that to people. Unless you like being cursed.

Full disclosure – I still do this from time to time. If anyone who extensively uses a screen reader reads this article, can you do me a favor and let me know your opinion on this?

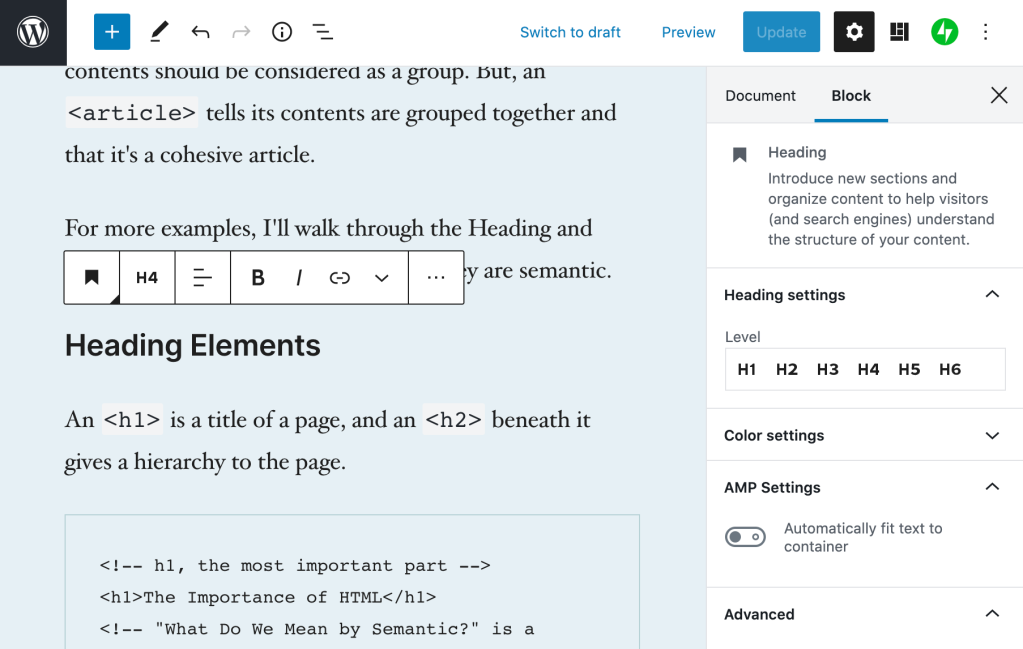

Use ARIA Landmark Roles

ARIA roles give a little extra info to screen readers. Some people say you only need to use them when the HTML5 semantics don’t already communicate it.

For example, those people argue that if you’re marking up your navigation with <nav>, then you don’t need to do <nav role="navigation"> because you already communicated that the element is a navigation with the HTML5 semantics.

However, the semantics only go as far as the screen reader program wants to follow those semantics.

“But,” you say, “they should follow the rules! I don’t want to write extra code when they should follow the rules!”

“Now, gentle reader,” I soothe, “let me tell you a little story about Internet Explorer.”

Let’s actually not do that. But, overall, it’s a minor inconvenience to communicate the information twice and hope all screen readers follow whichever semantics they do use correctly.

Here’s an example of how to markup most websites with ARIA roles:

<header role="banner">

<nav role="navigation">

<!-- your navigation -->

</nav>

<form role="search">

<label for="search">Search</label>

<input type="search" id="search" name="search">

<input type="submit" value="Search">

</form>

</header>

<main role="main">

<!-- show 'em that sweet, sweet content -->

</main>

<aside role="complementary">

<!-- Hey! I want you to see this stuff, but this isn't why you're here. -->

</aside>

<footer role="contentinfo">

<!-- I'm the footer, where the copyright, contact info, and whatever else you want to jam down here goes -->

</footer>

Pretty painless stuff.

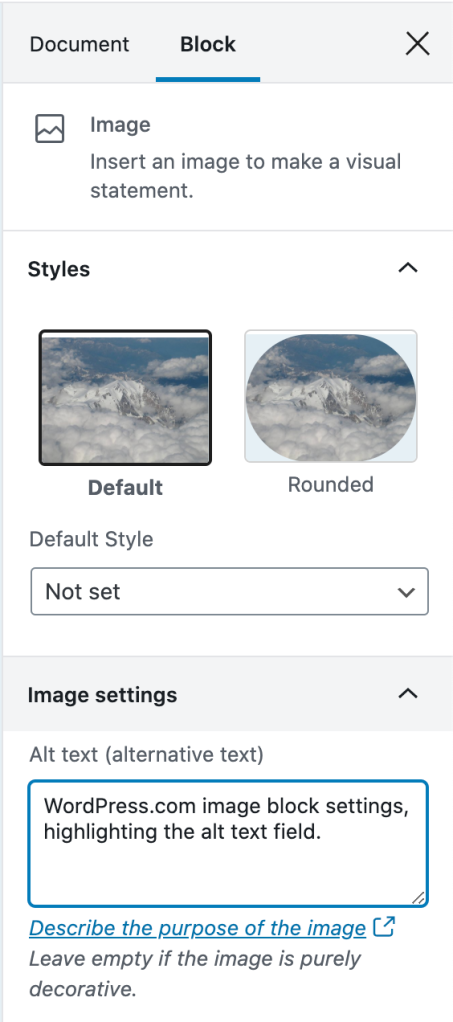

Add Extra Screen Reader Content to Give Context

Our visual designs often use space to give meaning and relationships between items. A screen reader can’t interpret our intentions, just what’s in the content. So, read through your site and ignore the visual layout (ideally, read through the source code). Does it make sense without those icons? If not, add some content, but visually hide it so it doesn’t clutter up your design.

To visually hide content but still let screen readers read it, add this to your CSS file:

/* Text meant only for screen readers */

.screen-reader-text {

clip: rect(0 0 0 0);

overflow: hidden;

position: absolute;

height: 1px;

width: 1px;

}

.screen-reader-text:hover,

.screen-reader-text:active,

.screen-reader-text:focus {

background-color: #f1f1f1;

border-radius: 3px;

box-shadow: 0 0 2px 2px rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.6);

clip: auto !important;

color: #21759b;

display: block;

font-size: 1em;

font-weight: bold;

height: auto;

left: 5px;

line-height: normal;

padding: 1em 1.6em;

text-decoration: none;

top: 5px;

width: auto;

z-index: 100000;

}

/* This code is taken from the Underscores WordPress theme and then adjusted from code from... I can't remember. Can anyone help me here? */

Then, whenever you want to add content for screen readers to give context but hide it visually, just add the “screen-reader-text” class to your element and you’re done!

<h3 class="screen-reader-text">Connect with Me on Social Media</h3>

<ul class="social-icons">

<!-- social media icons here -->

</ul>

Hide Unnecessary/Repeated Content from Screen Readers

In the same boat as hiding content visually but showing it to screen readers, sometimes we need to hide content from screen readers that’s really helpful in our visual designs.

For example, I like giant images, icons, and pull-quotes (repeated content) as much as the next designer, but, when using a screen reader, it doesn’t add to the content. Fortunately, it’s really easy to hide it from screen readers. Just add this code to any element you want to hide.

role="presentation" aria-hidden="true"

Here’s the markup I use for my social media icons in my footer. First, I use the screen-reader-text class (example earlier in the article) to hide “Connect with Jeremy Jones” because the context of the social icons suggest that to users who can see it, then I hide the social media icons from screen readers and offer them the social media site name instead. Here’s the code:

<h3 class="screen-reader-text">Connect with Jeremy Jones</h3>

<ul class="social-icons">

<li class="twitter">

<a href="https://twitter.com/juryjowns">

<i role="presentation" aria-hidden="true" class="icon-twitter"></i>

<div class="screen-reader-text">Twitter</div>

</a>

</li>

</ul>

I’ve also written a tutorial on creating accessible pull-quotes that uses this method.

Use Skip to Content Links

Using our “screen-reader-text” class above, we can now add a visually-hidden link that allows people on screen readers to skip over the header and go straight to the good stuff. Otherwise, when using a screen reader, you have to cycle through the whole header and navigation each time you go to a new page.

Here’s how to do it:

<a class="screen-reader-text" href="#main">Skip to content</a>

<!-- logo & navigation -->

<main id="main" tabindex="-1">

<!-- sweet, sweet content -->

</main>

The tabindex=”-1″ and linking to the HTML5 main element is important, unfortunately, to fix a bug in Chrome.

Test it With a Screen Reader

If you’re on a Mac, fire up VoiceOver by pressing Command+F5.

Control+Option are called the VO keys. When interacting with VoiceOver, you pretty much always press Control+Option and another key, so VO = Control+Option. Here are the key things to use when testing a website with VoiceOver:

- VO+Space = Click

- VO+Right Arrow = Focus next item (basically like a tab)

- VO+Left Arrow = Focus previous item (aren’t you glad you didn’t remove those focus outlines?)

- VO+Shift+Down Arrow = Interact with area. For example, if you click a tab, you need to use this to get into the content of the page. Or, just use your cursor to click the logo or a navigation link to bring the focus onto the content if you get stuck mashing keys that don’t seem to do anything.

- VO+U = Opens a “rotor” that lets you scan through headings, links, and some other stuff. Kind of like an automatically generated table of contents. Use the arrow keys to navigate through them. Definitely worth checking out.

If you want to learn more, WebAIM has a guide on using VoiceOver.

If you use semantic HTML, you should be happy to find that 95% of your site works just fine. If you don’t use semantic HTML, well… you’ll see.

For New Projects, Design Content-First

This tip isn’t a quick tip for retrofitting an accessible site, but if you care about accessible sites, then I can’t stress this enough. If you design by creating your content first, then code your HTML before doing any visual design, your site is going to be more accessible without even trying. Well-coded, semantic HTML is accessible out of the box.

Learn More

It’s hard, if not impossible, to make a perfectly accessible website for 100% of users, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try. You can learn a lot more tips and info on web accessibility by checking out the Accessibility Project.

Are there any great tips that I missed? Do you think I’m giving bad advice? I’m not looking to be right, I’m looking to provide a really useful article to help people easily make their websites more accessible. Let me know in the comments or on twitter if there’s something I can do to improve it.

![Playlist with current track highlighted and "[track title], current item, button, [podcast title], group" in the screen reader area.](https://jerryjones.dev/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/podcast-player-current-item-1.gif?w=1024)

![Navigating the buttons with the screen reader to see that the current track displays "Playing: [track title]"](https://jerryjones.dev/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/podcast-player-playing.gif?w=640)

![Screen reader showing "Loading: [track title] [track description]" when a new track is selected.](https://jerryjones.dev/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/podcast-player-loading.gif?w=640)